"Nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes"-- Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin was a can-do, jack-of-all-trades kind of fellow, who may have made the above statement only after failing to circumvent those "certainties". Cryonicists often cite Franklin's dream of being preserved in a cask of wine so that he could be reanimated in a world of more advanced technology. After reading Thomas Tryon's WAY TO HEALTH, Franklin adopted a vegetarian diet. Franklin was healthy, wealthy and wise enough to live to the age of 84 at a time when average life expectancy was less than 40 (he died in 1790). Franklin had the words "food for worms" placed on his tombstone.

Cryonics is an expensive proposition, particularly because so few people practice it that economies of scale are not possible. One can only speculate about the extent to which lower costs would result in larger numbers of cryonicists. Antiquated belief-systems or negative attitudes toward life are other reasons frequently given for why cryonics is not more popular. Yet another reason, however, is the fact that many people simply don't want to think about their mortality.

Approximately 60% of the adult population have done no estate planning. In fact, an estimated 60% of people die without having made a will. I suspect that the reasons for this are that (1) death is unpleasant to think about, (2) death seems remote and less pressing to plan-for than events in the near future and (3) most people probably don't believe their estate is of much consequence. Cryonicists, at best, are people who have temporarily made the effort to address these issues, but once their cryonics arrangements are in place, often give the matter no more thought. They may, in fact, only have addressed questions concerning their estate because they were required to do so in the cryonics sign-up process.

Cryonics CANNOT be funded directly from an estate. Estate money is subject to probate, which means that funds will not be available in a timely manner to pay for cryopreservation. Those who have money that would go into an estate who wish to arrange for cryopreservation have three options: (1) Prepay the required funds to a cryonics organization before the time of death (2) Obtain a Life Insurance Policy naming a cryonics organization as beneficiary. (3) Create a Trust having a cryonics organization as beneficiary. The first option is the simplest. The second option is a variant of the first if the insurance policy is fully funded (as would be required for an elderly person for whom the premiums would be terribly expensive). The third option may be too complicated to be practical for cryonic cryopreservation, although a perpetual trust could be created for money available upon reanimation (or to pay for reanimation).

Literally speaking, a will is a stated intention or desire (usually in written form) concerning disposition of assets. A testament is a covenant (binding agreement). (The OLD TESTAMENT & NEW TESTAMENT are purported covenants between God & Man -- promises from God, and conditions to be fulfilled by Man.) In practice, however, the words will and testament are used interchangeably. (A testamentary trust is a trust created by a will.)

A person who has died with a valid will is said to have died testate. A person who dies without a valid will is said to have died intestate. The man who signs his will is called a testator (testatrix, if female). A will can be declared invalid on grounds that the testator/testatrix was under the age of majority (18 in Ontario), was not of sound mind, or on grounds that the will was not properly witnessed (where witnesses are required). In Ontario, a holographic will (a will entirely in the handwriting of the testator, and signed by the testator -- no witness required) is valid, although it may be necessary to prove that the handwriting is indeed that of the testator/testatrix. Holographic wills are not valid in British Columbia. A "video will" is valid in some American states, but not in Canada.

A court certifies that a will is valid by issuing a sealed document known as "Letters Probate". (Probate comes from the Latin "probatio", which in canon law means "proof of a will".)

Letters Probate not only confirm the validity of a will, but confirm the executor (or executrix, if female) named in the will. It is the job of the executor/executrix to "administer" the estate, ie, to follow the instructions of the deceased in assembling the estate in a form for distribution, and in distributing the estate. In practice, this means determining (and liquidating) all the assets & debts of the deceased, including bank accounts, mortgages, stocks & bonds, pension benefits, unpaid wages & employment benefits, etc. Subscriptions & charge accounts must be terminated, and charge cards destroyed. Income taxes for the year of death must be paid, along with funeral expenses. A "notice to creditors" on 3 consecutive weeks in a local newspaper is a standard means by which an executor/executrix avoids liability from creditors making claims after all estate assets have been distributed.

If real estate is owned in more than one province or state, separate probate proceedings will be required for each jurisdiction. United States "situs property" would also include stocks & bonds, debts owed by US residents to the deceased, and any other personal property located in the US (cars, bonds, jewelry, etc.). These asses will be subject to US Estate Tax.

The executor/executrix also arranges for burial. Funeral directors are accustomed to waiting for a court grant from the estate in payment for services.

In Ontario, individual an individual executing an estate is entitled to 5% of the net income distributed to the beneficiaries. Typical fees charged by lawyers for probating an estate are less -- possibly because lawyers can do it so much more efficiently. Using the scales of the County of York Law Association, probate costs for an estate of average complexity would be:

ESTATE SIZE | $10,000 | $50,000 | $100,000 | $500,000 | $1 million |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INDIVIDUAL PROBATE (5%) | $500 | $2,500 | $5,000 | $25,000 | $50,000 |

| LAWYER PROBATE COST | $300 | $1,100 | $2,100 | $5,600 | over $7,000 |

When the executor/executrix is also a beneficiary, the administrative fees can be collected as part of the estate payment, and is thereby tax-free. Beneficiaries therefore often prefer to probate the will themselves rather than hire a lawyer.

In addition to the fees paid to the executor/executrix, the estate must also pay a fee to the provincial courts for issuing Letters Probate (a covert "death tax"). Typical fees (May 1997) would be:

ESTATE SIZE | $10,000 | $50,000 | $100,000 | $500,000 | $1 million |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | $25 | ? | ? | ? | $6,000 |

| British Columbia | $200 | $350 | $1,050 | $6,650 | $13,650 |

| Manitoba | $55 | $295 | $595 | $2,995 | 5,995 |

| Ontario | $50 | $250 | $1,000 | $7,000 | $14,000 |

| Quebec | $65 | $65 | $65 | $65 | $65 |

| Saskatchewan | $70 | $350 | $700 | $3,500 | $7,000 |

One of the functions of a will is to name an executor/executrix. If a person dies intestate, a probate court will appoint an administrator (rather than an executor/executrix) to administer the estate. By having no will, the intestate person loses the opportunity to select beneficiaries of the estate. Probate costs will be higher, and taxes are often higher as well.

Provincial courts all have rules for distribution of the estate of a person who dies intestate. Most provinces honor the concept of "preferential share", meaning the amount of the estate paid to a spouse before distributions are made to children or other relatives. As of January, 1997, preferential shares were:

| Alberta | $ 40,000 |

|---|---|

| British Columbia | $ 65,000 |

| Manitoba | $ 50,000 |

| Ontario | $ 200,000 |

| Quebec | $ 0 |

| Saskatchewan | $ 100,000 |

For all provinces the residue (after preferential share) would be equally shared by spouse and child if there is one child. For example, for a $100,000 estate in Alberta, the spouse would get $70,000 ($40,000 + $30,000) and the child would get $30,000. For 2 or more children, the spouse gets a third of the residue in all provinces but Manitoba (where she gets half). If there is no spouse, the children share the estate. Otherwise, money goes to siblings or parents, then nieces and nephews. If no family members are found, the money goes to the provincial government.

A person who dies testate, however, can name the beneficiaries he or she pleases. A spouse has special status and can (using the legal jargon) elect against the will within 6 months after the death of the other spouse. Most provincial laws will allow a spouse up to 50% of the estate. Other family members can challenge a will, but such a challenge will generally only succeed if they can prove that they were dependent upon the deceased. A common-law spouse has no grounds to elect against the will, but may successfully challenge the will if dependency can be proven. A popular myth holds that a will can be defended against a challenge from a family member by making that member the beneficiary of $1 from the estate. Only spousal relationship or dependency are criteria for changing the distribution of assets from beneficiaries specified in the will.

People concerned about the fact that a spouse can claim 50% of the collective family assets immediately after marriage should strongly consider a prenuptial agreement. A "prenup" is a legally binding agreement signed by both parties entering a marriage acknowledging specific assets owned by each spouse-to-be. It is a good idea to have the agreement reviewed by an estate-law and/or family-law attorney in your province or state.

Divorce proceedings rather than informal separation could also be a financially prudent action. Canada has "no-fault" divorce (a marriage is dissolve if one spouse so desires).

A codicil is an amendment to a will. Changing beneficiaries or distribution of assets in a codicil increases the chances that a beneficiary will challenge or contest the will. Changes beneficiary or asset distribution should be done through a new will. The best case for the use of a codicil is for changing an executor or the guardian of a minor.

A so-called "living will" is NOT a will at all. It is a misnamed document that records the kind of medical intervention you want to receive if you are unable to communicate your wishes due to mental or physical incapacity. A living will is often ignored by hospitals.

A power of attorney gives another individual the legal power to make decisions on your behalf. A power of attorney can be restricted to a specific piece of property, or there can be a general (also called "encompassing") power of attorney for all of your property. You can also grant an independent power of attorney for health care.

The strongest form of power of attorney is the durable power of attorney (also called "continuing"), so-called because it continues to be valid when you are in a state of incapacity. Although hospitals can sometimes ignore a living will, they find it much more difficult to ignore someone with durable power of attorney for health care. If you want to plan for a vegetative state, find a trusted person to be your durable power of attorney for health care.

Planning for an incapacitated state might also include disability insurance. Like many things many of us would rather not think-about, most people don't want to think about (and therefore don't plan for) the possibility of being in a disabled condition. Waiver of premium on a life insurance is valuable for this purpose, because if you are unable to work, you may find it difficult to maintain payments on the life insurance policy you have for cryonics funding.

|

A trust is a means for an owner of property to separate the control aspect of a property from the benefit aspect of that property. For example, a dying parent might create a trust for a young child (to be controlled by a trust company) which would be directed to pay yearly income for child support from the trust until the child reached a pre-specified age. Sometimes parents create trusts for their "adult children" who they do not believe can wisely manage money (due to a handicap or a reckless nature). Such trusts are often called "spendthrift trusts".

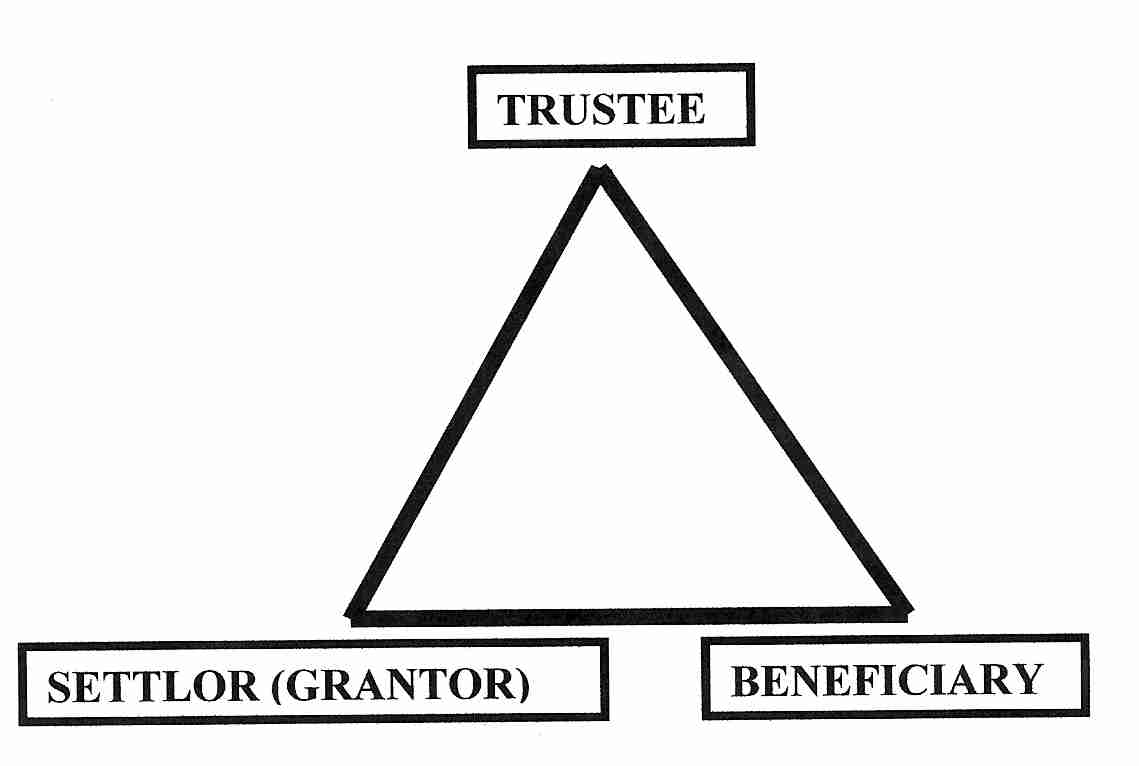

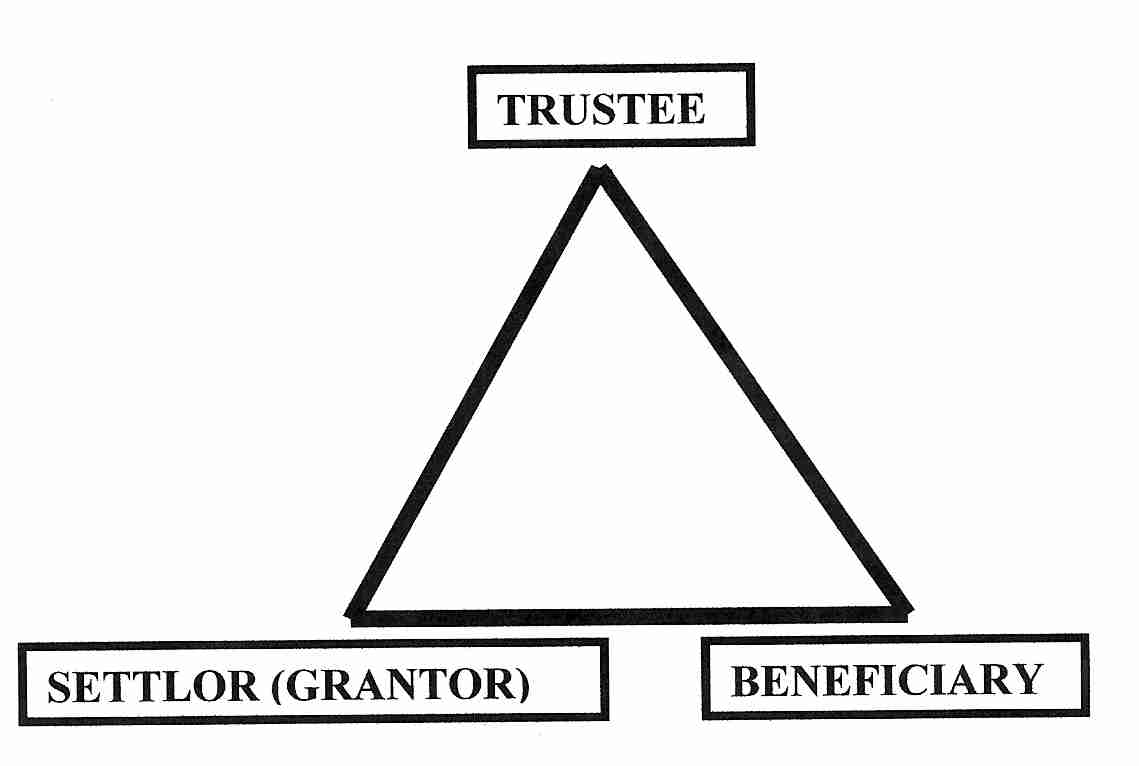

As originally conceived a trust has three parties:(1) the Settlor (who creates the trust from his/her property), (2) the Beneficiary (who receives ultimate benefits of the trust and (3) the Trustee, who controls the trust without receiving the benefits of the assets. (A Settlor is also known as a grantor, trustor or donor). Any 2 of the 3 parties of a valid trust can be the same legal entity. A Settlor who was Trustee, would lose the benefit of the property in the trust while maintaining control. For a "living trust" the Settlor and the Trustee are the same person. A Trustee who is Beneficiary would be expected to honor the terms of the trust document in distributing assets to himself/herself and the other Beneficiaries (if there are others). A common reason for a Settlor to also be a Beneficiary is the desire to have the assets managed by someone else, in the hope of counting on a worry-free flow of income in the future (even in the case of debility).

Alcor Foundation has 501(c)3 status, meaning it is recognized as a charitable institution for education and/or research by the US Internal Revenue Service (IRS). When someone dies and names a beneficiary in a life insurance policy, probate is bypassed and there will be no taxes on the proceeds if the beneficiary is a person. Proceeds are taxable for a corporate beneficiary, except if the beneficiary is a registered charity -- in which case the money is counted as a charitable gift. Money to Alcor is therefore a "gift", which the members hope Alcor will use for long-term maintenance and reanimation. However, if this project succeeds, Alcor members will be "born-again, naked & penniless", because Alcor cannot return what was given to them as a gift.

Claims have been made that Alcor's 501(c)3 status could easily be revoked because its cryopreservation activities do not serve a general charitable purpose of either education or research. But Alcor ex-President Steve Bridge assures me that 501(c)3 status is very rarely revoked, once it has been given. Ironically, Robert Ettinger failed in his attempt to get 501(c)3 status for the Cryonics Institute, and ruefully opines that it didn't really qualify. [The Immortalist Society does have 501(c)3 status.]

For a long time there was a concern that Alcor could spend money earmarked for cryopreservation on general expenses. For that reason the "Alcor Patient Care Trust" was created in May 1997. This is a somewhat unusual trust insofar as Alcor is the Settlor, the Beneficiary ("on behalf of the patients") and the Trustee is a "separate legal entity within Alcor". The Trustee is the Alcor Patient Care Trust, which is able to share Alcor's 501(c)3 status. Evidently Alcor's lawyers have determined that a separate legal entity within a corporation is a legally valid option. Alcor's trust was revocable until May 4, 1999, after which it becomes irrevocable. For money-management, the Alcor Trust contracts with Smith Barney's "Consulting Group". It is an Arizona trust (the "law against perpetuities" is not relevant since none of the Alcor organizations are expected to "die").

The American Cryonics Society has all of its members create testamentary charitable trusts (charitable trusts created by wills). Insurance policies name ACS [a 501(c)3 organization] as the beneficiary of immediate cryopreservation expenses -- and the charitable trusts are named as the beneficiary of long-term cryopreservation expenses. ACS is the Trustee of these charitable trusts and the members are the beneficiaries. Charitable trusts are exempt from the "law against perpetuities" and presumably reanimated ACS members would be able to collect any residual funds from the trusts. But for charitable trusts to stand up in court, they must be proven to benefit the public at large. So far there has been no court challenge.

CryoCare Foundation decided that 501(c)13 [cemetery] status would be a more defensible charitable status for a cryonics organization than 501(c)3. But after a long court battle, the IRS ruled that neither CryoCare Foundation nor the Independent Patient Care Fund (IPCF) could have cemetery status, because they are in the reanimation business. (The IRS should have solicited opinions from the Society for Cryobiology.)

In the late 1990s CryoCare/IPCF faced the necessity of individual trusts for its members. IPCF could have received insurance benefits without taxation if it had charitable cemetery status. (If the IRS was consistent, IPCF would only have to pay taxes upon delivery of reanimation service.) But individual trusts could receive insurance benefits without being vulnerable to taxation.

I investigated the possibility of individual trusts in Liechtenstein, which has no laws against perpetuities. But trust accounts have a minimum fee of US$4,500. Individual trusts could be pooled for the minimum fee, but cannot be pooled for the US$750 annual tax on individual trusts by the Liechtenstein government.

As of late 2005 there were nearly 20 American states that had abolished the law against perpetual trusts ("perpetuities") [KIPLINGER'S RETIREMENT REPORT; 12(5) (May 2005)] and other states have greatly increased the duration of trusts (Florida 360 years, Nevada 365 years and Wyoming 1,000 years). The nearly 20 states reported by Kiplinger as no longer having a law against perpetuities were: Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Delaware, Idaho, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Ohio, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Virginia, Wisconsin and the District of Columbia. A CARDOZO LAW REVIEW study (Volume 27, 2006) found that abolition of the Generation-skipping transfer tax of 1986 created a salient tax advantage on long-term trusts and that states abolishing the law against perpetuities significantly increased their trust business. This explains the recent surge of states to allow perpetual trusts and implies that more states may allow long-term trusts in the near future.

Only two of the states with no law against perpetual trusts have no state income tax: Alaska and South Dakota. Alaska, however, has corporate income tax, and Alaska trusts are generally more expensive. The absence of state income tax not only avoids tax on income, it reduces trustee administrative costs in preparing tax returns.

The June 16, 1997 issue of FORBES magazine contained a very good overview comparing trust law features between states in the US. At the end of the article there is a color-coded map of the United States which summarizes the features. As should be clear from the map, about all that Wisconsin has going for it is Unlimited trust duration (ie, no law against perpetuities). The Uniform Probate Code is a negative -- a requirement that trusts be registered in a state court. Delaware has no such requirement, but the trusts that are of must interest to us (irrevocable trusts and post-mortem trusts) aren't probatable and needn't be registered.

Aside from having state income tax, Wisconsin is one of the states that has a state gift tax. I had much trouble getting straight answers from people in Wisconsin, especially about taxes, and I suspect that the complexity of the matter there plus a higher regulatory burden is at the root of the problem. Since part of annual trust costs is preparation of tax returns, total annual fees would be expected to be higher in Wisconsin. Wisconsin is at the bottom of my list of preferred perpetual trust states, just below Idaho.

From the trust map it would appear that South Dakota affords less protection from creditors than Delaware or Alaska. But the main vulnerability of irrevocable or post-mortem trusts for cryonics patients would probably be attacks by relatives. Delaware law, it turns out, is very soft- hearted about breaking trusts for the sake of a spouse or child-support. I heard a similar story in Alaska. An Alaska trust officer told me that the best protection is to have the spouse sign a document declaring that he or she has no beneficial interest in the trust.

The Uniform Prudent Investor Act gives statutory support for trust administrators to be relieved of money management responsibilities. Since we want the option of doing our own money management, this would seem to make Alaska look less favorable. But Alaska House Bill 197 brought the Uniform Prudent Investor Act to Alaska. Even without this statute, however, the Alaska Trust Company Fee Schedule lists fees for delegated money management while stressing that "The trust document must specifically exonerate and hold harmless Alaska Trust Company from any investment responsibility, liability or duty."

For people willing to pay for the luxury of having a mechanism for keeping assets out of probate, the expense of an annual fee for a revocable living trust is justified. By being revocable, assets can be moved in & out of the trust at will, and the assets & earnings of the trust are still part of the person's assets & income for tax purposes. Creation of an irrevocable trust, however, is a means of removing trust assets from one's taxable estate and trust income from taxable income. Although irrevocable trusts are usually created to reduce taxes, they could conceivably be of use for cryonics purposes if the named beneficiaries were cryonics service providers (for immediate care) and a cryonics trust for perpetual maintenance (or funds could simply remain in the trust and be designated for that use).

|

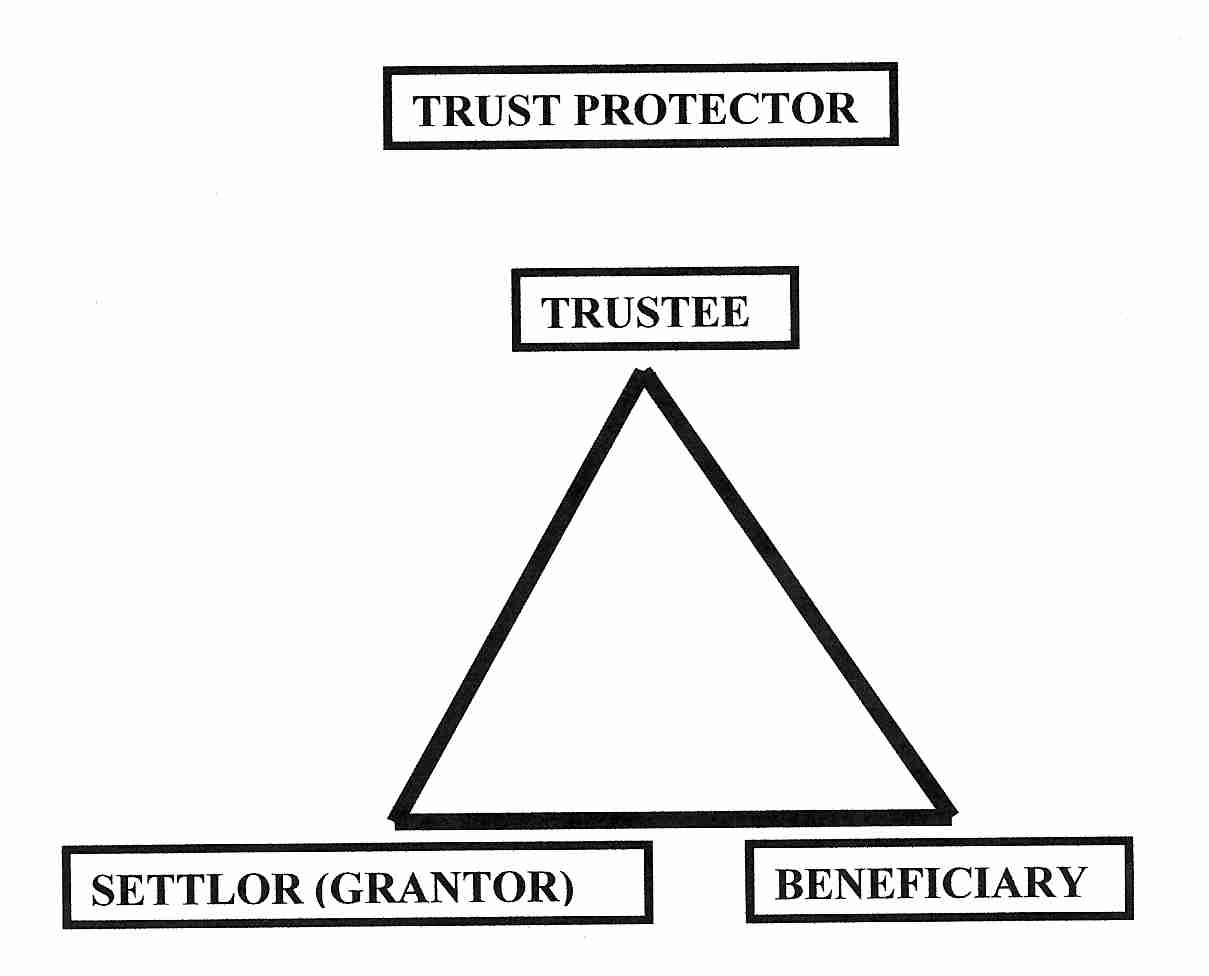

Unlike classical trusts, a perpetual trust allows for the existence of a 4th party to the trust: the Trust Protector. The Trust Protector has the power to change Trustees and to change Beneficiaries. Changing the beneficiary might be useful if laws change affecting the nature of the entity allowed to be Beneficiary. But can you trust the Protector?

A perpetual trust provides the means for a cryonicist to allocate money to reanimation costs as well as provide for wealth upon reanimation. There are potential problems in having the Settlor and Beneficiary being the same person, with the Beneficiary being a legally dead person when the trust comes into effect. For CryoCare a corporation called the Independent Patient Care Foundation (IPCF) was created which could act as Beneficiary for all of the individual trusts and do individual accounting for each of the trusts. The IPCF also served as the Trust Protector.

Trusts must name an alternative Beneficiary, and if poorly chosen the alternative Beneficiary could sue the trust. Could sue on grounds that the cryopreservation was botched or ineffective or sue on grounds that trust assets were mismanaged. An alternate Beneficiary must be chosen who is guaranteed not to sue. The Trustee must be in the same state as the trust, eg, a South Dakota Trustee. How trustworthy is the Trustee? An untrustworthy Trustee could deplete assets by poor investments or active stock trading intended to generate commissions. CryoCare was able to be a co-Trustee with a South Dakota bank.

The question of taxes invariably arises when discussing American domestic trusts. Canada does not have estate taxes, but the United States has estate taxes which have a noticeable "soak the rich" orientation. Trust companies (in the US and offshore) mainly expect to be dealing with wealthy folks seeking to reduce taxes. (And they charge accordingly.)

As of 1998, the basic exemption from US Estate taxes is $625,000. This exemption will be gradually increased to $1 million by the year 2006. To prevent the wealthy from evading estate taxes through pre-mortem gifts, gift taxes were created. Thus, an individual has a lifetime exemption to a Unified Estate & Gift Tax (in 1998) of $625,000. However, gifts less than $10,000 to any one individual in any single year are not included, although any excess over $10,000 will be included. Gifts to trusts are completely excluded from the $10,000 yearly exemption (but are included in the lifetime exemption). For example, if a person gave $10,000 to 3 people, $50,000 to one person and $5,000 to a trust in a single year, $40,000 of the last person's gift and $5,000 placed in the trust would be included in the $625,000 exemption (or count towards taxable estate if the $625,000 exemption has already been used-up).

Case law, however, has established an exception to the taxability of gifts to trusts (the case of the California Crummey family in Crummey vs. Comm, 1968). If a beneficiary of a trust is given 30 days notice and the right to withdraw funds deposited in the trust, then the money placed in the trust qualifies for the $10,000 annual gift tax exemption. (This will work so long as the beneficiary does not withdraw the money!) Trust companies often charge extra for making yearly mailings of Crummey notices for the irrevocable living trusts they maintain. Cryonicists who are wealthy enough to have problems like this to worry about should be wealthy enough to pay for their solution. Cryonicists with estates under US$600,000 (or under US$1 million in a few years) needn't concern themselves with these matters.

Another form of trust which might be of interest for cryonics purposes is the Life Insurance Trust. Such trusts typically have a life insurance policy as the primary asset. Although life insurance proceeds are not taxable, they are included in the $625,000 basic exemption of the deceased. An irrevocable living trust, however, is a separate legal entity. With an irrevocable life insurance trust the proceeds of the contained insurance policy are not included in the estate, in calculating the exemption. However, the payment of the premiums on the included insurance policies are taxable if Crummey provisions are not claimed, since premium payment would be a "gift" to the trust (not a problem for someone with an estate far less than $625,000).

Unlike the United States, Canada has no Estate Taxes. These were abolished in Canada in the 1970s. But Canadian tax laws are structured in such a way as to take a far larger bite out of the assets of the deceased than American Estate Taxes do. Before any assets can be distributed to the estate, they must be deemed liquidated with all accumulated capital gain assigned to the final income tax return of the deceased.

For example, imagine that the deceased purchased stocks at $10,000 thirty years ago and a cottage at $16,000 twenty years ago. If the stocks are now worth $110,000 and the cottage is worth $216,000, there will be $100,000 capital gain on the stocks and $200,000 capital gain on the cottage. Capital gains are taxed by adding 75% of the gain to taxable personal income. Therefore, the personal taxable income of the deceased will be increased 0.75 X$300,000 = $225,000 of which about 50% will go to Federal and Provincial taxes.

Registered Retirement Pension Plans (RRSPs) are worse. All assets from an RRSP must be liquidated and 100% of the proceeds added to the taxable income of the deceased before distribution to the estate. An RRSP can, however, bypass the estate and probate by having a person as the named beneficiary. If a man named his daughter as the beneficiary of his RRSP, the liquidated RRSP would go directly to the daughter, reducing his own final tax statement and reducing probate costs. But the daughter would have to pay tax on 100% of the RRSP proceeds as an addition to her taxable income. The only way to avoid probate and all RRSP taxes is to name one's spouse as the beneficiary. Only a person can be named as an RRSP beneficiary (not an organization). A Canadian wishing to use RRSP proceeds to augment cryonics funding will have to allow the RRSP to be liquidated, taxed in the final tax return, added to the probated estate and then distributed to the cryonics organization (or a cryonics trust). [An RRSP is, nonetheless, a good way to accumulate tax-sheltered money for income in the later years of life. But it is taxed very heavily if death occurs before it can be used for that purpose.]

A life insurance policy, however, can name a cryonics organization as beneficiary. Life insurance proceeds are paid fairly quickly, and they bypass the estate as well as probate. Naming your estate as the beneficiary of a life insurance policy and then attempting to direct payment of estate proceeds to a cryonics organization is not a good idea. Besides increasing the vulnerability of the assets and the costs of probate, the money would be subject to delays on the order of 6 months (a typical duration of the probate process).

Cryonicists have often thought of creating trusts which could hold assets during their period of cryopreservation. Most jurisdictions have "laws against perpetuities" which prohibit the creation of trusts that do no end after a certain period of time (after the death of the youngest Beneficiary, for example). Canada has one province that has no law against perpetuities: Manitoba. But Canada would be a very bad choice of a country for creation of a cryonics trust.

In Canada, a trust is taxed as if it is a separate taxpayer not entitled to any personal exemptions. A living trust (trust existing while the Settlor is still alive) is taxed at the top combined Federal and Provincial rate -- amounting to about 50% of annual income. A testamentary trust (a trust created by a will) can avoid the highest tax rate by deferring capital gains if the beneficiary is a spouse. Beginning in 1999, however, all Canadian trusts are required to pay taxes on all deferred capital gains every 21 years -- as if all capital assets had been liquidated.

Individual trusts have the greatest potential for flexible provision of funding for reanimation and "walking-around money" after reanimation. Terms of the trust can be written to suit the means & desires the individual cryonicist. Nonetheless, suitable provisions for defending the funds of a person who is legally dead (and thus without legal standing) are still in doubt. Cryonic cryopreservation itself is best funded by insurance or prepayment rather than by a trust.