by Ben Best

|

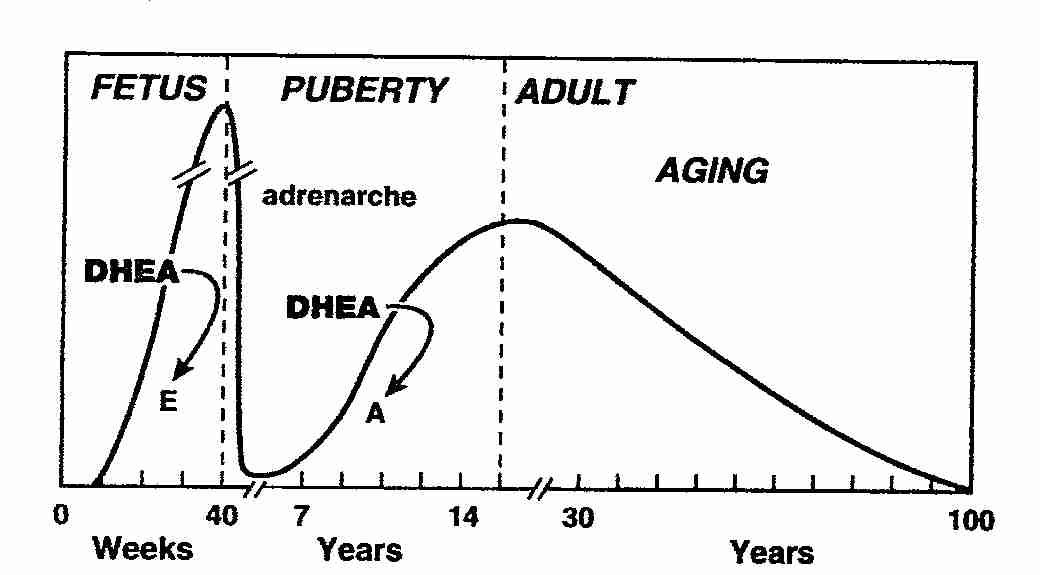

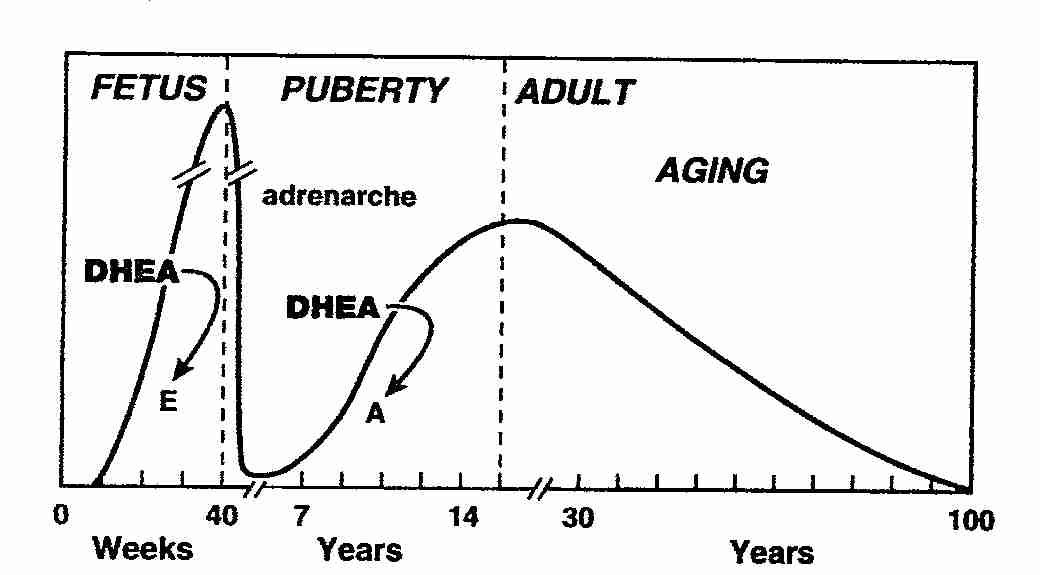

DeHydroEpiAndrosterone (DHEA) and its sulfate (DHEAS) are the most abundant steroid hormones in the human bloodstream. Blood levels are highest in the developing foetus, drop sharply after birth, begin climbing again at age 6−8 (a time of rapid growth) to a peak at age 25−30 and then decline to about 10% of the peak level by age 80. Adult blood levels of DHEAS are 100−500 times higher than testosterone and 1,000−10,000 times higher than estradiol [THE JOURNAL OF ENDOCRINOLOGY; Labrie,F; 187(2):169-196 (2005)].

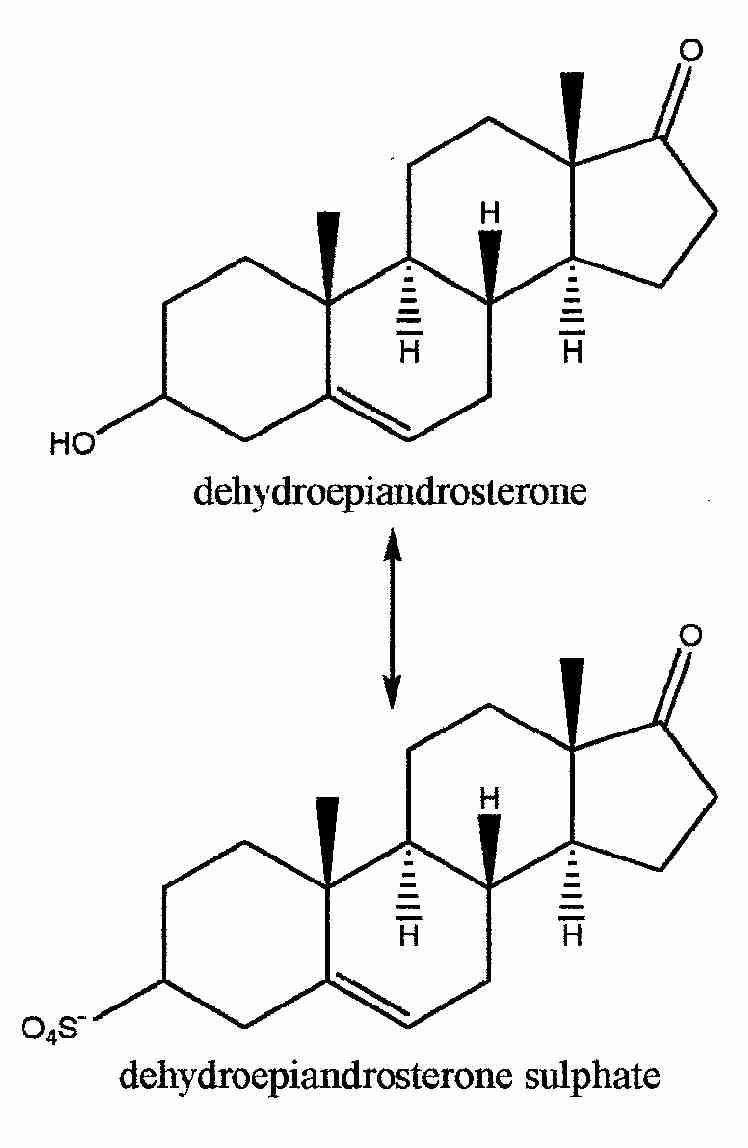

DHEA circulates in the bloodstream mainly as the sulfated form, DHEAS. The half-life of DHEAS is 7−10 hours, whereas the half-life of DHEA is only 15−30 minutes. DHEAS is coverted to DHEA and then to sex hormones in body tissues. No change in DHEAS serum levels is seen beyond the age of 90, and men over 90 with the highest serum DHEAS levels show the best functional status [THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY & METABOLISM; Ravaglia,G; 81(3):1173-1178 (1996)].

With the exception of high-affinity G-protein DHEA receptors on endothelial cells, there are no receptors for DHEA, which some have interpreted as meaning that it serves mainly as a precursor to other hormones. A sense of futility (or acceptance) concerning aging-associated functional decline, the diversity & vaguely-understood nature of DHEA actions and the fact that DHEA is a natural hormone that cannot be patented have all contributed to the relative lack of research that has been done on the value of DHEA hormone replacement.

About half of the body's DHEA is produced in the adrenal cortex — with the rest coming from gonads, fat tissue and (notably) the brain. The steroid synthesis pathway is:

cholesterol -> pregnenolone -> DHEA -> testosterone -> estrogen

|

Humans have considerably higher levels of DHEA than any other species. Even non-human primates produce not much more than 10% of the DHEA that humans produce. Sex hormones are produced almost exclusively by the ovary & testes of most mammals, whereas for humans (and to a lesser extent some other primates) about half of the sex hormones come from the gonads and about half is synthesized on an as-needed basis from DHEA in peripheral tissues (breast, prostate, brain, muscle, liver, etc.) For post-menopausal women, DHEA is the only source of sex hormones in peripheral tissues.

(For more about sex hormones and menopause, see Sex Hormone Replacement in Older Adults.)

Animal studies have indicated beneficial effects of DHEA against diabetes, atherosclerosis, osteoporosis, cancer and reduced immune function [AGE AND AGING; Steel,N; 28(2):89-91 (1999)]. Mice have shown neither an increase nor a decrease in cancer or longevity with DHEA treatment [CANCER RESEARCH; Pugh,TD; 59(7):1642-1648 (1999)]. But the relatively tiny amounts of DHEA in laboratory animals and the distinctly human role of DHEA makes animal studies suspect.

Concern has been expressed that DHEA may be like other hormones in contributing to cancer risk, despite the association between low serum DHEA and breast cancer found in epidemiological studies [BMJ; Weksler,ME; 312(7035):859-860(1996)]. Epidemiological studies indicate a correlation between mortality & health with blood DHEA levels, which is especially high in male smokers [PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES (USA); Mazat,L; 98(14):8145-8150 (2001)].

In one study 82% of women compared to 67% of men have reported improved "well being" (better sleep, more energy, better able to handle stress) when taking DHEA [BMJ; Weksler,ME; 312(7035):859-860(1996)]. A 50 mg DHEA per day four-month double-blind study of women having low DHEA due to adrenal gland insufficiency showed significantly reduced anxiety & depression leading to reduced exhaustion. Increased sexuality was associated with androgenic effects. The improvements were seen after four months, but not after one month — indicating the value of the longer-term study [NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE; Arlt,W; 341(14):1013-1020 (1999)].

Although it has been proposed that reduced DHEA may result in increased insulin resistance, it has been shown that insulin increases DHEA clearance — suggesting that low DHEA could simply be a consequence of insulin resistance [EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ENDOCRINOLOGY; Tchernol,A; 151(1):1-14 (2004)]. Another small study showed improved insulin sensitivity, endothelial function and fibrinolytic activity for middle-aged men with high cholesterol taking 25 mg per day for 12 weeks [THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY & METABOLISM; Kawano,H; 88(7):3190-3195 (2003)]. But a larger on normal elderly subjects lasting 2 years showed no such benefits — suggesting either that there is no DHEA benefit in normals or that short-term benefits are not sustained [NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE; Nair,KS; 355(16):1647-1659 (2006)]. Elderly humans given 50 milligrams of DHEA daily for two years showed decreased insulin resistance and reduced inflammatory cytokines compared to those given placebo [AGING; Weiss,EP; 3(5):533-542 (2011)].

The aforementioned NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE study by Nair was greeted by many as proof positive that DHEA supplementation is of no value. Double-blinded and placebo-controlled, the study compared roughly 30 each of elderly men & women on DHEA against the same number of controls (about 30 men and 30 women) over a 2 year period. No adverse effects were found and no benefit was seen for bone mineral density, body muscle-fat composition, physical performance, insulin resistance or quality of life. The study did acknowledge some bone mineral density increase, but this result was dismissed as inconsequential. Another placebo-controlled, double-blind study of almost the same size and study population lasting 6 months using 50 mg/day of DHEA on elderly men & women showed significant decreases in visceral & subcutaneous fat as well as increases in insuling sensitivity and IGF−1 levels — suggesting that DHEA may be of use against the metabolic syndrome [JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION; Villareal,DT; 292(18):2243-2248 (2004)].

Three months of 50mg daily DHEA for men and women showed a 10% elevation in serum IGF-1 [CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY; Morales,AJ; 49(4):421-432 (1998)]. But a full year of 50mg daily DHEA showed no positive effect on either muscle strength or muscle cross-sectional area [ARCHIVES OF INTERNAL MEDICNE; Percheron,G; 163(6):720-727 (2003)]. (DHEA may be a safer means of raising serum IGF-1 than growth hormone replacement.)

Although another widely-cited study also found no improvement in body composition or psychological well-being, it did note changes in blood values deemed of no clinical significance [THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY & METABOLISM; Flynn,MA; 84(5):1527-1533 (1999)]. In another placebo-controlled study of middle-aged men & women suffering from depression there was a significant improvement with at least 90 mg/day of DHEA [ARCHIVES OF GENERAL PSYCHIATRY; Schmidt,PJ; 62(2):154-162 (2005)]. A 26-week study that found no general improvement in mood or cognitive function in normal men aged 62−76 noted that a higher morning cortisol/DHEA was associated with greater anxiety & confusion and that DHEA may attenuate the effects of cortisol [PSYCHONEUROENDOCRINOLOGY; van Niekerk,JK; 26(6):591-612 (2001)]. (There are serious concerns about the long-term effect of cortisol on the hippocampus, see Hormones and Aging.)

The NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE study by Nair that dismissed DHEA supplementation as being without value made no assessment of endothelial function, effects of cortisol on the hippocampus, of immune function, of skin status and of a number of other parameters.

DHEA (50 milligrams/day) in a small study of 20 diabetic patients reduced plasma reactive oxygen species, the reactive aldehyde hydroxynonenal (HNE), and the Advanced Glycation End-product pentosidine by about 50% [DIABETES CARE; Brignardello,E; 30(11):2922-2927 (2007)].

DHEA has been shown to improve blood vessel endothelial cell function (vasodilation) through specific G−protein−coupled receptors that activate endothelial cell nitric oxide synthetase activity [JOURNAL OF BIOLOGICAL CHEMISTRY; Liu,D; 277(24):21379-21388 (2002)]. Cultured human endothelial cell proliferation is increased by DHEA by a mechanism independent of the actions of testosterone or 17β−estradiol — and postmenopausal women receiving 100 mg DHEA per day for 3 months showed significantly increased endothelium-mediated vascular reactivity in both large & small blood vessels [THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY & METABOLISM; Williams,MRI; 89(9):4708-4715 (2004)].

DHEA is produced in the brain by neurons & astrocytes (mainly by astrocytes) [ENDOCRINOLOGY; Zwain,IH; 140(8):3843-3852 (1990)]. Neurogenesis continues in adult life in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, a process that is inhibited by ethyl alcohol and cortisol, but which is stimulated by DHEA [THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF NEUROSCIENCE; Karishma,KK; 16(3):445-453 (2002)]. DHEA acts by decreasing glucocorticoid receptor levels in the hippocampus, rather than by competing with glucocorticoids at receptors [PHYSIOLOGICAL RESEARCH; Celec,P; 52:397-407 (2003) ]. And DHEA strongly increases the density of dendritic spine synapses in the CA1 field of the hippocampus of ovariectomized female rats [ENDOCRINOLOGY; Hajszan,T; 145(3):1042-1045 (2004)]. By this mechanism DHEA protects hippocampal cells from glutamate and amyloid−β toxicity [PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY FOR EXPERIMENTAL BIOLOGY AND MEDICINE; Cardonnel,A; 222(2):145-149 (1999)].

In contrast to more modest immune-boosting results for women, a single-blind, placebo-controlled study of healthy, nonsmoking men in their 50s & 60s taking 50 mg of DHEA daily showed rejuvenation of the immune system by increased secretion of the cytokine InterLeukin-2 (IL−2), which is a potent T-cell growth factor. Natural Killer (NK) cells showed a 22% increase — and stimulated InterLeukin−6 (IL−6) was increased [JOURNALS OF GERONTOLOGY; Khorram,O; 52A(1):M1-M7 (1997)]. Similar effects were seen in rodent studies [ANNALS OF THE NEW YORK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES; Spencer,NF; 774:200-216 (1995)]. An inverse correlation is seen between blood levels of DHEA and the pro-inflammatory cytokine (IL−6) — and a U−shaped relationship is seen between IL−6 production & DHEA in tissue cultures of human monocytes & mononuclear cells [THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY & METABOLISM; Straub,RH;83(6):2012-2017 (1998)]. Although some improvement in immune function has been shown for women, studies of a possible weak association with increased cardiovascular risk in women has raised concern [JOURNAL OF CLINICAL EPIDEMIOLOGY; Johannes,CB; 52(2):95-103 (1999)].

Women suffering from lupus erythematosus have shown a significant reduction in disease flares if taking 200mg/day DHEA rather than placebo [ARTHRITIS AND RHEUMATISM; Chang,DM; 46(11):2924-2927 (2002)]. Older women (and to a lesser extent men) taking 50mg/day DHEA showed significant improvement in skin status (hydration, sebum production, epidermal thickness) over a one-year period [PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES (USA); Baulieu,E; 97(8):4279-4284 (2000)].

Canada has declared DHEA to be an "anabolic steroid" that is illegal to own or sell without a prescription in that country. DHEA is sold without prescription in the United States. Supplementation with massive amounts of DHEA (1600 mg/day) has caused such serious effects as reducing thyroid-binding globulin and HDL cholesterol while increasing insulin resistance [THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY & METABOLISM; Mortola,JF; 71(3):696-704 (1990)]. Even 100 mg/day has caused hot flashes and chest pains [THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY & METABOLISM; Wolf,OT; 82(7):2363-2367 (1997)]. A safe and reasonable dose of DHEA for men over 40 might be 25-50 mg per day. For women, the question is more controversial.